AN OFTEN IGNORED ASPECT OF QUALITY IN U.S. PATENTS: DRAWINGS

As I have written previously, quality is paramount in the overall value of a United States patent. Let’s face it, the United States is a litigious country, and the expenses associated with enforcing or defending an infringement accusation can literally bankrupt a person or company involved in litigation. It makes no sense, therefore, to skimp when it comes to maximizing the quality of a patent. A well-written and carefully prosecuted patent stands a better chance of avoiding lengthy and expensive litigation insofar as the parties involved are likely to acknowledge the futility of fighting in court over the breadth of coverage, validity, and/or enforceability of that patent.

One aspect of a patent that is often overlooked concerns the figures/drawings of the patent. The United States Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) often accepts hand-drawn figures, so long as they meet certain requirements. But that doesn’t mean it is a wise move on the part of the applicant/patentee. A reality of the judicial system in this country is that, in patent litigation, those in charge of deciding the fate of the patentee’s assertions of infringement are rarely technically savvy, and that reality makes the role played by the figures in a patent critical to the full understanding of the invention.

In a typical patent litigation in the U.S., one of the first formal dispositive and substantive decisions in the action is a Markman hearing, in which a federal judge decides on the interpretation of the patent claims asserted to be infringed. Statistically, the chances that the federal judge assigned to the Markman hearing has a scientific or engineering background are minimal, to state the least. Assuming that the above-named proceeding results in a claim interpretation that favors the patentee’s position, there is still another major obstacle. At the end of the process, it is a jury made up of members of the public, that ultimately decides whether or not the accused product pr process infringes the claims of the patent. Once again it is worth noting that most members of a typical jury in this country lack any formal scientific or engineering training. The patentee (or rather his lawyers) is faced with an uphill battle needing to educate the non-technically educated members of the jury about technical aspects and about how those aspects form part of the claimed invention, to then take the next step in explaining how the accused product or process infringes the claims of the patent. That task is made far more difficult when the patent in question has an insufficient number of figures or simply inadequate figures.

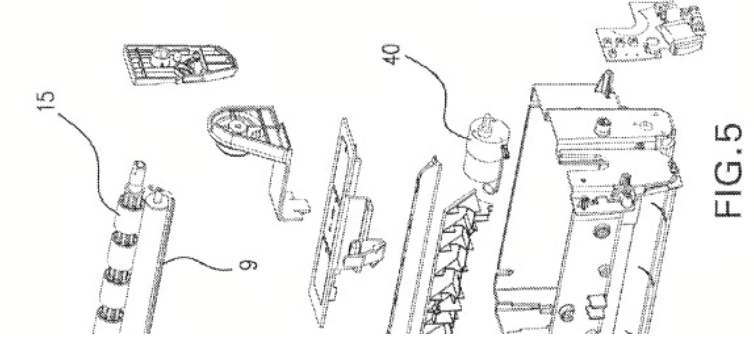

In my many years practicing in this area, I have often come across patent figures showing the product covered by the patent as a fully disassembled object; one that may include walls, springs, washers, screws and many other components essentially floating in space. See an example below (and this is not the worst I have seen):

Understanding the invention embodied in the figures in such patents often required the reader to engage in a difficult mental exercise to put the disassembled object back together and visualize how the various features interact with one another. Is it reasonable then to expect a non-technically savvy judge or member of a jury to similarly engage in that type of mental exercise in order to fully understand the claimed invention?

Patent figures of the type described above may be acceptable in certain jurisdictions, in which the judges assigned to patent litigation cases almost always, by design, tend to be technically trained. But that is not the case in the U.S. In light of the high costs of patent litigation in this country, and the gigantic nature of monetary damages involved, having inadequate figures in your patent is simply asinine. If you are spending money to obtain a patent, make sure to include high quality drawings. Your patent value will ultimately depend on them.